Music MattersA blog on music cognition

A blog on music cognition, musicality and related matters.

2026

If musicality did not arise from language, where did it come from?

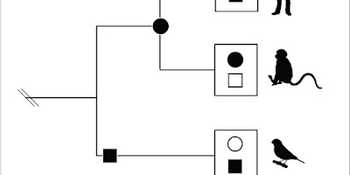

Comparative studies have revealed that components of musicality have distinct evolutionary histories: primate research supports gradual development of rhythmic and audiomotor integration, while convergent traits in vocal-learning species highlight shared biological constraints.

Neuropsychological and developmental findings have further shown that musicality is not reducible to language, drawing instead on perceptual, motor, and affective systems that likely predate speech.

Collectively, these insights establish musicality as a fundamental cognitive capacity and provide a robust framework for investigating how its components evolved, how they function across species, and why music is central to human life.

But, if musicality did not arise from language, where did it come from? Will be out soon in Current Biology (Honing, in press).

Honing, H. (2026, in press) The biology of musicality.

doi: 10.31234/osf.io/j8x4w.

Drawing courtesy of Marianne de Heer Kloots (mdhk.net).

No progress since Darwin and Spencer?

Asif Ghazanfar and Gavin Steingo open their recent Commentary in Science, by asserting that –because no fossil or archaeological record of early music-making exists– modern musicality researchers “rely as much on conjecture as they did in Darwin and Spencer’s time.”

This characterization is inaccurate.

The evolution of musicality can be reconstructed using methods from comparative biology, genetics, and cross-cultural analyses, empirical domains that were unavailable to Darwin and Spencer.

Over the past twenty years, musicality research has shown that virtually all humans have a natural capacity for music (1, 2), comparable to our innate capacity for language. Examples include beat processing in human newborns (3), species-specific precursors of both rhythmic and pitch processing (4, 5), and showing cross-cultural ‘universals’ in the structural aspects of human music (6–8), suggesting a biological basis. Additionally, recent neuroscientific findings indicate that humans process speech and music through distinct — and possibly independently evolved — neural pathways (9). Together, these findings constitute a robust empirical foundation rather than conjecture and have substantially reshaped our understanding of musicality.

While trained tapping in macaques (10)—as discussed in Ghazanfar and Steingo’s Perspective—addresses only one subcomponent of musicality, it nonetheless offers a valuable window into its evolution, particularly within the framework of the Gradual Audiomotor Evolution (GAE) hypothesis (11). This hypothesis proposes that beat perception and synchronization emerged through incremental increases in the connection between cortical and subcortical motor planning regions. Probing beat perception and isochrony perception in animals is still in its infancy, but it appears, at least within the primate lineage, that beat perception has evolved gradually, peaking in humans and present only with some limitations in chimpanzees and other non-human primates (12, 13).

Lastly, the relevant object of inquiry here is not music per se, but musicality. For this reason, Ghazanfar and Steingo’s analogy comparing the study of music evolution to ‘human bike evolution’ is unhelpful. Riding a bike requires explicit training even in humans, whereas moving to a musical beat emerges spontaneously and effortlessly, often before the onset of language. This spontaneity is precisely what places beat perception so prominently within musicality research. In other primates, beat perception is not effortless but can be acquired through training, suggesting that for them it is analogous to bike riding in humans. As the authors note, studying trained abilities can nevertheless reveal the basic processes underlying those abilities. More generally, both spontaneous and trained behaviors in animals offer complementary insights into their evolutionary capacities: humans spontaneously acquire speech but can be trained to imitate bird calls, indicating a specialized drive for conspecific communication alongside a broader capacity for vocal imitation. Similarly, non-human primates possess timing and pattern-detection abilities that may form the evolutionary substrate from which human beat induction emerged. Overall, comparative research across cultures and across species provides a powerful framework for uncovering the biological foundations and evolutionary history of musicality.

As a result, investigating the origins of musicality has become increasingly feasible. What was once a largely speculative corner of musicology has developed into a rapidly advancing interdisciplinary field, rich with compelling new research questions.

References

- H. Honing, C. ten Cate, I. Peretz, S. E. Trehub, Without it no music: cognition, biology and evolution of musicality. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 370, 20140088 (2015).

- W. T. Fitch, Four principles of bio-musicology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 370, 197–202 (2015).

- I. Winkler, G. P. Háden, O. Ladinig, I. Sziller, H. Honing, Newborn infants detect the beat in music. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106, 2468–71 (2009).

- C. ten Cate, H. Honing, “Precursors of music and language in animals” in The Oxford Handbook of Language and Music, D. Sammler, Ed. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2025; https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/59773).

- M. Hoeschele, H. Merchant, Y. Kikuchi, Y. Hattori, C. ten Cate, Searching for the origins of musicality across species. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370 (2015).

- J. H. McDermott, A. F. Schultz, E. A. Undurraga, R. A. Godoy, Indifference to dissonance in native Amazonians reveals cultural variation in music perception. Nature 25, 21–25 (2016).

- P. E. Savage, S. Brown, E. Sakai, T. E. Currie, Statistical universals reveal the structures and functions of human music. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 8987–8992 (2015).

- N. Jacoby, E. H. Margulis, M. Clayton, E. Hannon, H. Honing, J. Iversen, T. R. Klein, S. A. Mehr, L. Pearson, I. Peretz, M. Perlman, R. Polak, A. Ravignani, P. E. Savage, G. Steingo, C. J. Stevens, L. Trainor, S. Trehub, M. Veal, M. Wald-Fuhrmann, Cross-cultural work in music cognition: Challenges, insights and recommendations. Music Percept 37, 185–195 (2020).

- P. Albouy, L. Benjamin, B. Morillon, R. J. Zatorre, Distinct sensitivity to spectrotemporal modulation supports brain asymmetry for speech and melody. Science (1979) 367, 1043–1047 (2020).

- V. G. Rajendran, L. Prado, J. Pablo Marquez, H. Merchant, Monkeys have rhythm. Science (1979) 390, 940–944 (2025).

- H. Merchant, H. Honing, Are non-human primates capable of rhythmic entrainment? Evidence for the gradual audiomotor evolution hypothesis. Front Neurosci 7, 1–8 (2014).

- H. Honing, F. L. Bouwer, L. Prado, H. Merchant, Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) sense isochrony in rhythm, but not the beat. Front Neurosci 12 (2018).

- Y. Hattori, M. Tomonaga, Rhythmic swaying induced by sound in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 936–942 (2019).

2025

Are humans unique?

In The Unique Animal, Rens Bod revisits an age-old philosophical question: what makes us human? His answer is that our uniqueness lies in unbounded recursion—which, according to Bod, is the defining feature that fundamentally distinguishes humans from all other animals.

Recursion is undoubtedly an elegant notion, with a long and rich intellectual history, which gained renewed momentum in the second half of the twentieth century through, among others, Douglas Hofstadter’s influential book Gödel, Escher, Bach, Mandelbrot’s theory of fractals, and Chomsky’s claim that recursion is the only truly distinctive property of the human language faculty.

Yet I wish to argue that this very search for uniqueness—for a single capacity that defines us—is a misleading enterprise. However intriguing recursion may be, it does not provide the solid foundation that some believe it does.

1. The problem of uniqueness

All animal species are unique. In that sense, we humans are unique as well—but not more so than other animals. Uniqueness is not rare; it is ubiquitous. The attempt to single out one exclusive feature in humans is therefore a peculiar, perhaps even pretentious, endeavor. The history of thought is full of such attempts—from Aristotle’s rational animal to Chomsky’s syntactic animal. But these efforts often reveal more about our desire to draw boundaries than about reality itself. We like to draw a sharp line between “human” and “animal,” while nature rarely complies.

2. Recursion and its limits

Recursion is without doubt a fascinating phenomenon, both mathematically and cognitively: the capacity to have thoughts about thoughts and to embed sentences within sentences. In theory, this allows infinite complexity to emerge from finite means—an influential idea.

But empirical reality is far less unbounded. Humans can process only a few levels of embedding—three, at most four—before losing track. In language, we lose the thread after the third subordinate clause; the same applies to reasoning and play. We can still follow that someone is pretending to pretend, but add yet another layer and we are lost.

Unbounded recursion therefore does not describe how the human brain actually functions. Rather, it is a theoretical idealization—a concept that helps describe grammars and other hierarchical patterns in behavior, without necessarily contributing to deeper understanding. (The trees of linguistics have more than once prevented us from seeing the forest of our cognitive capacities.)

3. The problem of testability

This leads to a more fundamental objection: unbounded recursion is not empirically testable. No experiment can demonstrate its existence, let alone falsify it, because every human performance is by definition finite. Nor can it be refuted, since any limitation can always be explained away as a matter of attention or memory. Thus the concept slips from the hands of science and drifts into the realm of metaphysics—into belief in something that may be true, but cannot be proven. For that reason, we must reject the thesis on rational grounds: not out of reluctance, but because a scientific explanation must be testable—or rather, falsifiable.

4. Beyond the linguistic lens

There is, moreover, another important factor at play: a widespread and persistent language bias in our thinking—a tendency I have pointed out before and written about elsewhere. Many researchers prefer to view cognitive phenomena through a linguistic lens. Because formal language systems are characterized by recursive structures, it is then often assumed that thought—and thus the human mind—must be recursive in nature. But cognition is more than language.

Music offers an interesting counterexample. Music also exhibits hierarchical structures—structures characterized by multiple levels of organization, repetition, variation, and symmetry. These properties are not uniquely human: songbirds and various marine mammals structure their vocalizations in ways that show striking similarities to human music and can be regarded as precursors of our musical capacity. Hierarchy, however, is not synonymous with recursion. Although the two concepts are closely related, there is an essential difference: recursion presupposes a hierarchical structure, but a hierarchy need not be recursive.

5. A different idea of uniqueness

Perhaps we should therefore abandon the search for a single, exclusive feature and understand uniqueness differently—not as something belonging solely to humans, but as an emergent phenomenon arising from the convergence of multiple capacities. What makes humans special, then, is not one isolated property such as recursion, but a specific combination of components that together form a unique whole. From this perspective, the question shifts from “What do humans have that other animals do not?” to “Which capacities make a species unique?” Our uniqueness is not a single essence, but an evolutionary pattern—a fabric of gradually developed capacities that together form the basis for culture, language, and music.

Epilogue — in relation to The Arrogant Ape

In The arrogant ape, Christine Webb dismantles the deeply rooted human tendency to overestimate our own exceptionalism. Humans, she argues, are not the pinnacle of evolution but one species among many—remarkable, yes, but not categorically superior. What Webb calls “arrogance” is precisely the urge critiqued in the column above: the desire to locate one decisive trait that elevates us above all other animals. In short, abandoning the myth of the uniquely gifted human does not diminish us. On the contrary: it situates us more accurately within the living world, as one expressive, musical, meaning-making species among many—remarkable not despite that continuity, but because of it.

Bod, R. (2025). Het unieke dier: Op zoek naar het specifiek menselijke. Amsterdam: Prometheus.

Webb, C. (2025). De arrogante aap: Waarom we niet zo uniek zijn als we denken. Amsterdam: Atlas Contact.

See also https://hdl.handle.net/11245.1/e38e36c0-4c95-4f7c-a3fa-5c890f5b5b7f.

Musical Animals: Are we? Can there be?

On November 20, 2025, the Royal Palace Amsterdam hosted the symposium “Music and Mind, Music as Medicine,” part of the ongoing series organized by the Amsterdam Royal Palace Foundation. The event brought together leading voices reflecting on how music shapes thought, health, and human experience.

I had the honour to present the opening keynote, “Musical Animals: Are We? Can There Be?”, about musicality as a natural, biological capacity. I explored the question of whether humans are truly unique in perceiving rhythm and melody—or whether other species share aspects of what we call “music.”

You can listen to the keynote here: Download audio file [or go to Royal Palace website].

Prof. Em. Daniel J. Levitin followed with insights from neuroscience and psychology, connecting music to memory, emotion, and healing. His perspective added valuable depth to the symposium’s theme of music as medicine.

The day was further enriched by a powerful performance from Dame Evelyn Glennie, whose artistry and reflections on listening brought the scientific discussions into vivid, lived experience.

Special thanks were due to Tania Kross and Prof. Ineke Sluiter, who co-chaired the symposium and guided the conversations with clarity and warmth.

Altogether, the event offered a meaningful window into how music—whether studied in labs, performed onstage, or felt in our bodies—continues to inspire new questions and connections.

All recordings can be found at the wesbite of the Royal Palace.

A draft article, with the same title, can be found here as preprint.

![Gaat muzikaliteit aan muziek én taal vooraf? [Dutch]](/static/3d2a2495a79305851112dc6da7dcf3f4/ed594/woe(2).jpg)

Gaat muzikaliteit aan muziek én taal vooraf? [Dutch]

Hoe het brein van onze verre voorouders

eruitzag, is niet meer na te

gaan. Toch is er via een omweg

misschien iets te zeggen over het

ontstaan van taal, en de rol die

muziek daarbij speelde.

Veel taalkundigen geloven —vreemd genoeg— dat onze liefde voor muziek meelift op ons taalvermogen (zie bijvoorbeeld NRC uit 2016 en Steven Pinker's invloedrijke boek How the mind works). Maar zou het niet, en even waarschijnlijk, precies andersom kunnen zijn?

Voor een overzicht van de recente ontwikkelingen op het gebied van de neurowetenschappen van taal en muziek, zie bijv. Peretz et al. (2015), Norman-Haignere et al. (2015) en de video hieronder: een registratie van de lezing Voor de muziek uit die ik in 2016 gaf op het tweejaarlijkse congres Onze Taal in het Chassé Theater in Breda.

N.B. Een samenvatting van de tekst verscheen in het tijdschrift Onze Taal. De integrale tekst verscheen in het interdisciplinaire tijdschrift Blind.

Norman-Haignere, S., Kanwisher, N., & McDermott, J. (2015). Distinct Cortical Pathways for Music and Speech Revealed by Hypothesis-Free Voxel Decomposition Neuron, 88 (6), 1281-1296 DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.035

Peretz, I., Vuvan, D., Lagrois, M., & Armony, J. (2015). Neural overlap in processing music and speech Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370 (1664), 20140090-20140090 DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0090

Can birds imitate Artoo-Detoo?

When you think of birds imitating sounds, parrots and starlings might come to mind. They’re famous for copying human speech, car alarms, and even ringtone melodies. But what happens when you challenge them with something really complex, like the electronic beeps and boops of R2-D2, the beloved Star Wars droid? Researchers from the University of Amsterdam and Leiden University put nine species of parrots and European starlings to the test.

<div>

Starlings versus parrots

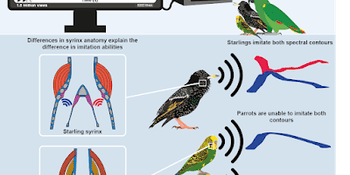

It turns out that starlings had the upper hand when it came to mimicking the more complex 'multiphonic sounds. Thanks to the unique morphology of their vocal organ, the syrinx, which has two sound sources. This allows starlings to reproduce multiple tones at once—perfect for R2-D2-style chatter.

Parrots, on the other hand, are limited to producing one tone at a time (just like humans). Still, they held their own when it came to the simpler “monophonic” beeps of R2-D2. Interestingly, it weren’t the famously chatty African grey parrots or amazon parrots that did best, but the smaller species, like budgerigars and cockatiels. These little birds, often thought of as less impressive vocalists, actually outperformed the larger species in this specific task, likely by using different strategies to imitate sounds.

</div>

</div>

<div>

Even sounds from science fiction can teach us something real

The researchers call their study a fun but powerful window into how anatomy, like the structure of a bird’s vocal organ, can shape the limits and possibilities of their vocal skills. It is the first time that so many different species all produced the same complex sounds, which finally allows for a direct comparison. This shows that even sounds from science fiction can teach us something real about the evolution of communication and learning in animals.

And here’s the cool part: much of the sound data came from pet owners and bird lovers participating in citizen science through the Bird Singalong Project. With their help, the researchers were able to gather a richer, more diverse collection of bird sounds than ever before, proving that science doesn't always have to happen in a lab.

Reference

Piano touch unraveled. Touché?

[Adapted from interview by Elleke Bal, Trouw, 3 October 2025]

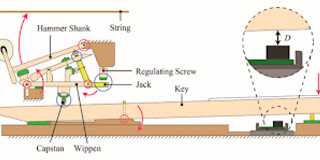

Two professional pianists may perform on the exact same piano, in the same concert hall, and even play the same notes at the same tempo. Yet, through the way they touch the keys, they are able to produce strikingly different sounds from the instrument.

This so-called timbre—the tonal color or quality of sound—has long been a subject of fascination and debate among musicians and listeners alike. Consider, for example, the crystalline clarity of Glenn Gould versus the warmth of Sviatoslav Richter. But what exactly constitutes clarity or warmth? For pianists, these are intuitive concepts. For scientists, however, the challenge has been to find objective evidence that such distinctions arise from unique motor actions at the keyboard.

The researchers examined which motor skills underpinned these differences. They found that timbral variation was strongly associated with a limited set of keystroke parameters: the velocity of key descent, the temporal spacing between successive key presses, and the synchrony between hands. Crucially, one factor emerged as particularly decisive: the acceleration of the key movement at the precise moment the hammer disengages. According to the authors, this acceleration largely determines the resulting timbre (Kuromiya et al., 2025).

This study demonstrates the extraordinary precision achieved by highly trained pianists. Nuances in timing and velocity of a few milliseconds can shape timbre in ways that are musically significant. These micro-timing differences are the product of extensive practice and experimentation at the instrument. However, the study overlooked one key factor: the velocity of the hammer striking the string. Without measuring hammer dynamics, the account of timbre remains incomplete. Companies such as Yamaha have long recognized this; their Disklavier Pro system, for example, replicates hammer velocity to convincingly reproduce the playing of pianists like Glenn Gould.

Ultimately, it is the hammer which, at the moment it is released from the piano’s action mechanism, independently carries the cumulative timing and dynamic input of the performer. Its subsequent trajectory toward the string—and the resulting timbre—is determined by its momentum, defined by the combined effects of its velocity and mass.

Does reducing the artistry of great pianists to numerical parameters diminish the magic of a performance? I don’t think so: This research only reinforces the extraordinary dexterity, control, and timing that distinguish master pianists.

References

Kuromiya, K., et al. (2025). Motor origins of timbre in piano performance, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.,122 (39) e2425073122, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2425073122

Goebl, W., & Palmer, C. (2008). Tactile feedback and timing accuracy in piano performance. Experimental Brain Research, 186 (3), 471-479 DOI: 10.1007/s00221-007-1252-1

![Was het vroeger allemaal anders? [Dutch]](/static/3e6a91a3f3c42374e4ecd2aaaa4af865/d5c9f/honing_2005_vulpennenbeheer.jpg)

Was het vroeger allemaal anders? [Dutch]

[N.B. Column uit 2005]

De faculteit verplicht vanaf heden iedere medewerker alleen nog maar te schrijven met een balpen van het merk Bic. De argumenten zijn: ze schrijven net zo goed als andere pennen, zijn een stuk goedkoper, behoeven zo goed als geen onderhoud, en mocht er dit toch nodig zijn dan heeft de faculteit een geolied team van Bic-experts in dienst. Vulpennen en potloden mogen niet meer gebruikt worden. Alleen na uitzonderlijke toestemming mag een medewerker zijn vulpen gebruiken maar onder de voorwaarde alleen op eigen papier te schrijven (‘inktvlekken zijn voor eigen risico; Bic’s vlekken niet’ zo zegt de ondersteunende afdeling).

Leest dit als een knullig fantasieverhaaltje? Vervang de Bicpen door een Windows-computer en de vulpen door bijvoorbeeld een Apple-computer en het voorbeeld beschrijft het huidige ICT-beleid van de faculteit. Wat is hier nu zo irritant aan? Dit soort beleid stamt uit een tijd dat een computer iets onbeheersbaars was, iets waar alleen bèta’s in stofjassen aan mochten komen. We zijn inmiddels zo’n dertig jaar verder en de computer heeft een belangrijke en soms haast persoonlijke plaats in onze dagelijkse denk- en werkruimte ingenomen. Een privédomein waaraan je specifieke en persoonlijke eisen stelt. Een werkgever die de inrichting en de mogelijke bewegingen in deze denk- en werkruimte bepaalt is niet meer van deze tijd.

Een voorbeeld. In mijn muziekonderzoek speelt de computer een grote rol. Naast een belangrijke rol in theorievorming wordt de computer regelmatig ingezet voor online internetexperimenten. Het formaat dat voor de geluidsvoorbeelden gebruikt wordt is MPEG4 (een internationale standaard die hoge geluidskwaliteit garandeert via zowel modem als DSL). Deze standaard wordt echter om strategische redenen (Microsoft wil zijn eigen standaards promoten) niet ondersteund op Windows-computers. De experimenten kunnen dus niet door de studenten en medewerkers op UvA-computers uitgevoerd worden. Met als concreet gevolg dat weinig studenten en medewerkers musicologie meedoen aan het onderzoek.

Dit soort restricties als gevolg van beleidskeuzes heeft zo z’n gevolgen. De trend die je ziet ontstaan is dat studenten en medewerkers UvA-DSL nemen en thuis in alle vrijheid hun laptop inrichten zoals zij dat willen. En aangezien een laptop niet aangesloten mag worden op het interne UvA-netwerk wordt zo het thuiswerken extra gestimuleerd (en onderhoud en beheer een privézaak).

Het beleid heeft echter ook grotere gevolgen dan irritaties bij studenten en medewerkers. Wederom een voorbeeld. Bij de onderhandelingen over een recentelijk toegekend onderzoeksproject van de EU met een grote technologische component, is om o.a. infrastructurele redenen besloten het project niet bij de faculteit geesteswetenschappen (FGw) maar bij de bèta wetenshcappen (FNWI) te plaatsen. Dat is erg jammer en het kan het onderzoek en onderwijs bij de FGw alleen maar verarmen.

Mijn (ongevraagd) advies is dan ook: leg overal in de faculteit WiFi aan, geef iedere studenten een high-tech laptop (met flinke korting), en laat iedereen vrijelijk experimenteren en downloaden. Mijn voorspelling: binnen twee jaar zijn er geen vaste computers én geen ondersteuning meer nodig, net zo min als er ooit een afdeling vulpennen-beheer nodig was.

Henkjan Honing (Amsterdam, April 2005)

![Hoezo geen ritmegevoel? [Dutch]](/static/b5a49d780497270633ad05ae4ceade73/a45e6/IMG_2154.jpg)

![Are there controversies in pitch and timbre perception research? [in 333 words]](/static/3319ecad06a063ef9d1ecfa39ca5b51f/532cd/sturnus-vulgaris.jpg)

Are there controversies in pitch and timbre perception research? [in 333 words]

At the heart of human musicality lie fundamental questions about how we perceive sound. In the coming academic year our group will dedicate several meetings on exploring and clarifying the spectral percepts that might underlie musicality with an agenda set around some enduring controversies. These span the roles of learning, culture, and cross-species comparisons, as well as evolutionary explanations for why music holds such sway over human minds.

Among the most debated topics is the relationship between pitch and timbre perception. Both pitch and timbre are percepts: mental constructs arising from acoustic input. In humans, pitch perception is central to melodic recognition. When we hear a melody, we tend to identify it by its sequence of relative pitches—hearing it as the “same” tune regardless of changes in timbre, loudness, or duration. This reliance on relative pitch is a cornerstone of human music cognition.

But is pitch such a universal perceptual anchor? For years, researchers assumed so, pointing to songbirds as an obvious parallel. Birds, it was thought, must also use pitch cues, though often in the form of absolute rather than relative pitch. Yet recent evidence complicates this narrative. In a striking study, Bregman et al. (2016) reported that European starlings do not, in fact, rely on pitch when recognizing sequences of complex harmonic tones. Instead, they appear to attend more closely to spectral shape, or the broader distribution of energy across frequencies.

This finding raises a further question: is it really the spectral envelope (i.e. spectral shape) that matters, or something more subtle? Because the methods used—particularly contour-preserving noise vocoding—leave open another possibility: birds may actually be attuned to fine spectral-temporal modulations, the intricate contours woven into sound. Such results remind us that perceptual categories humans take for granted may not map cleanly onto other species, and that the universality of pitch as a cognitive anchor remains an open, and fascinating, controversy (cf. Patel, 2017; ten Cate & Honing, 2025).

N.B. These entries are part of a new series of explorations on the notion of Spectral Percepts (in 333 words each).

Bregman, M. R., Patel, A. D. & Gentner, T. Q. (2016). Songbirds use spectral shape, not pitch, for sound pattern recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(6), 1666–1671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515380113

Patel, A. D. (2017). Why Doesn’t a Songbird (the European Starling) Use Pitch to Recognize Tone Sequences? The Informational Independence Hypothesis. Comparative Cognition & Behavior Reviews, 12, 19–32. doi: 10.3819/CCBR.2017.120003

ten Cate, C. & Honing, H. (2025). Precursors of music and language in animals. In D. Sammler (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Language and Music. Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780192894700.001.0001

![Is consonance a biological or a cultural phenomenon? [in 333 words]](/static/0f846b967cf250286c12de862b02db49/e21b2/chicks.jpg)

Is consonance a biological or a cultural phenomenon? [in 333 words]

The distinction between consonance and dissonance has long occupied a central place in the scientific study of auditory perception and music cognition. Consonant intervals are typically described as stable, harmonious, or pleasing, whereas dissonant intervals are often characterized as tense, unstable, or even harsh. Yet even these seemingly straightforward descriptions quickly lead to methodological debate.

A central difficulty arises from the frequent conflation of “dissonance” with “roughness.” Roughness refers to a physiological effect caused by closely spaced frequencies interacting on the basilar membrane of the inner ear. This phenomenon is measurable, consistent, and largely universal across listeners. Consonance, however, is not reducible to physiology alone. Recent research emphasizes that consonance is a multidimensional construct, shaped by both acoustic properties such as harmonicity and by layers of cognitive and cultural familiarity (Lahdelma & Eerola, 2020).

This controversy can be framed around two major questions (Harrison, 2021). First, do humans possess an innate preference for consonance over dissonance? Second, if such a preference exists, how might it be explained in evolutionary terms? A landmark study by McDermott et al. (2016) with the Tsimane’, an Amazonian group minimally exposed to Western music, found no consistent preference for consonant over dissonant intervals. Their conclusion was that what many listeners call “pleasant” is primarily shaped by cultural experience.

This interpretation has been vigorously challenged. Bowling et al. (2017) cite empirical evidence from human infants (Trainor et al., 2002) and even non-human animals (Chiandetti & Vallortigara, 2011) that points toward at least some innate, hardwired auditory sensitivity. If so, consonance may reflect evolutionary selective pressures, possibly related to the spectral composition of human vocalizations and the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying pitch perception and auditory scene analysis.

In the end, consonance appears to be neither purely biological nor purely cultural. Our ears detect roughness and harmonicity, but our minds interpret these sensations through cultural frameworks. What sounds stable in one tradition may sound unfamiliar in another. The consonance controversy thus highlights music cognition as an intricate interplay between biology and culture.

References

Bowling, D. L., Hoeschele, M., Gill, K. Z. & Fitch, W. T. (2017). The nature and nurture of musical consonance. Music Perception, 118–121.

Why does a well-tuned modern piano not sound out-of-tune?

"Neue Musik ist anstrengend", wrote Die Zeit some time ago: "Der seit Pythagoras’ Zeiten unternommene Versuch, angenehme musikalische Klänge auf ganzzahlige Frequenzverhältnisse der Töne zurückzuführen, ist schon mathematisch zum Scheitern verurteilt. Außereuropäische Kulturen beweisen schließlich, dass unsere westliche Tonskala genauso wenig naturgegeben ist wie eine auf Dur und Moll beruhende Harmonik: Die indonesische Gamelan-Musik und Indiens Raga-Skalen klingen für europäische Ohren schräg."

The definition of music as “sound” wrongly suggests that music, like all natural phenomena, adheres to the laws of nature. In this case, the laws would be the acoustical patterns of sound such as the (harmonic) relationships in the structure of the dominant tones, which determine the timbre. This is an idea that has preoccupied primarily the mathematically oriented music scientists, from Pythagoras to Hermann von Helmholtz.

The first, and oldest, of these scientists, Pythagoras, observed, for example, that “beautiful” consonant intervals consist of simple frequency relationships (such as 2:3 or 3:4). Several centuries later, Galileo Galilei wrote that complex frequency relationships only “tormented” the eardrum.

But, for all their wisdom, Pythagoras, Galilei, and like-minded thinkers got it wrong. In music, the “beautiful,” so-called “whole-number” frequency relationships rarely occur—in fact, only when a composer dictates them. The composer often even has to have special instruments built to achieve them, as American composer Harry Partch did in the twentieth century.

Contemporary pianos are tuned in such a way that the sounds produced only approximate all those beautiful “natural” relationships. The tones of the instrument do not have simple whole number ratios, as in 2:3 or 3:4. Instead, they are tuned so that every octave is divided into twelve equal parts (a compromise to facilitate changes of key). The tones exist, therefore, not as whole number ratios of each other, but as multiples of 12√2 (1:1.05946).

According to Galilei, each and every one of these frequency relationships are “a torment” to the ear. But modern listeners experience them very differently. They don’t particularly care how an instrument is tuned, otherwise many a concertgoer would walk out of a piano recital because the piano sounded out of tune. It seems that our ears adapt quickly to “dissonant” frequencies. One might even conclude that whether a piano is “in tune” or “out of tune” is entirely irrelevant to our appreciation of music.

[fragment from Honing, 2021; Published here earlier in 2012]

![What makes two melodies feel like the same song? [in 333 words]](/static/dad636affda4b4026d1b90b3e472edc2/5a35f/timbre%20space%20(Krumhansl%2C%201989).jpg)

What makes two melodies feel like the same song? [in 333 words]

One of the most intriguing questions in music cognition research is also one of the simplest: when are two melodies experienced as the same?

At first glance, the answer might seem obvious — they share the same notes, in the same order, with the same rhythm. But a closer look, across cultures and even across species, reveals a more complex picture. What our brains latch onto when recognizing a tune involves a web of spectral percepts — the fundamental features of sound that guide humans and other animals in interpreting auditory patterns. This may sound like a niche research topic, but it lies at the heart of debates about authorship, originality, and musical ownership.

Consider hearing a melody played in a different key or on an unfamiliar instrument. Most people can still recognize it. How is this possible? Explanations often point to intervallic structure — the sequence of pitch intervals between notes — the contour, which is the overall shape of a melody as it rises and falls, or timbre, often described as the “color” of sound, including brightness, texture, and loudness.

For decades, music research treated timbre as secondary — something layered over supposedly “meaningful” musical features like pitch and rhythm (cf. McAdams & Cunible, 1992). Increasing evidence now suggests timbre is not merely decorative but a core perceptual building block. Timbre may also support “relative listening,” the ability to track patterns of change across different features. Exploring it carefully could reveal flexible and universal aspects of music cognition previously underestimated.

Recognizing that humans and non-human animals may rely on different spectral cues is equally crucial for understanding music’s evolutionary roots. A melody meaningful to humans may not register as such for a zebra finch — and vice versa.

By broadening music cognition research to include timbre, spectral contour, and species-specific strategies, scientists hope to uncover the shared perceptual foundations of musicality. Such work moves us closer to answering a deceptively simple but deeply complex question: what truly makes two melodies feel like the same song?

References

McAdams, S, & Cunible, J-C (1992). Perception of timbral analogies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 336, 383-389.

Krumhansl, C. L. (1989). Why is musical timbre so hard to understand? In S. Nielzén & O. Olsson (Eds.), Structure and perception of electroacoustic sound and music (pp. 43– 53). Elsevier.

Want to test your musical memory?

Test your musical memory! A beta version of #TuneTwins is now online at https://tunetwins.app.

Note: Some things may still not work perfectly here and there. Please let us know via the feedback button – it helps us a lot!

Big thanks to Jiaxin, Noah, Bas, Ashley, Berit and the Music Cognition Group at large !

What do Bach, bipedalism and a baby crying have in common?

Feel free to join the BètaBreak on June 20th between 12:00 and 13:30 at Science Park 904, Amsterdam, to explore the relationship between music and time in an interdisciplinary discussion with insights from biology, evolution, musicology and philosophy with speakers from the University of Amsterdam, the University of Liverpool and the University of Oslo!

Music in our genes?

"In 1984, a curious study on musicality in animals was published. The researchers from Portland, Oregon trained pigeons to distinguish two pieces of music – one by Bach, the other by Stravinsky. If the birds got it right, they were rewarded with food. Afterwards, the same pigeons were exposed to new pieces of music from the same composers. Surprisingly, they were still able to determine which piece was composed by which composer.This finding confronted researchers with a new set of questions. To what extent are animals musical? What does it even mean for an animal to be musical? And what can this teach us about musicality in humans?"

(From Music in our genes, ILLC Blog).

What is the use of the comparative approach in studying the origins of language and music?

Comparative studies can be done in several ways. One approach is to examine the sounds made by animals and look for shared features or parallels with language or music. To study these, one can, for example, examine how the structure of a sequence of sounds compares to syntactic structures in language or rhythmic structures in music, or whether harmonic sounds are recognized by their pitch (like in music) or by their spectral structure (like in speech). The presence of such features can indicate that similar sensory or cognitive mechanisms may underlie their perception and production and those needed for language and music in humans. However, one needs to be cautious with drawing such conclusions. That a sound produced by an animal has certain features in common with language or music may be incidental and a result of human interpretation, rather than indicating shared mechanisms per se. Animal sounds showing, for example, a specific rhythmic pattern (e.g., in the call of the indri, a lemur species; De Gregorio et al., 2021) or that contain tones based on a harmonic series (e.g., in the hermit thrush; Doolittle et al., 2014), need not indicate an ability of the animal to perceive or produce rhythms or harmonic sounds in general, as is common in humans. To show this, it is necessary to demonstrate the perception or production of such patterns outside and beyond what is realized in the species-specific sound patterns. This requires a second approach: using controlled experiments to address whether animals can (learn to) distinguish and generalize artificially constructed sounds that differ in specific linguistic or musical features. The two approaches, observational-analytical and experimental, are complementary: the first one may hint at presence of a certain ability, while the second one can test its existence and the limits of the capacity (Adapted from: ten Cate & Honing, 2025).

De Gregorio, C., Valente, D., Raimondi, T., Torti, V., Miaretsoa, L., Friard, O., Giacoma, C., Ravignani, A. & Gamba, M. (2021). Categorical rhythms in a singing primate. Current Biology, 31(20), R1379–R1380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.09.032

Doolittle, E. L., Gingras, B., Endres, D. M. & Fitch, W. T. (2014). Overtone-based pitch selection in hermit thrush song: Unexpected convergence with scale construction in human music. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 11(46), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1406023111

Ten Cate, C. & & Honing, H. (2025). Precursors of Music and Language in Animals. Sammler, D.

(ed.) Oxford Handbook of Language and Music Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780192894700.013.0026. Preprint: psyarxiv.com/4zxtr.

![Wetenschap in de blogosfeer? [Dutch]](/static/db4ab21b234212638e731ae2402113dd/e21b2/folia.jpg)

Wetenschap in de blogosfeer? [Dutch]

"Ik weet niet direct wat muziekcognitie is, maar dat is geen probleem. Dit is een prima blog, gemaakt door een vakidioot die zo te zien met liefde over het onderwerp schrijft. Hij blogt niet veel, niet eens een keer per week, maar wel uitgebreid en nauwkeurig. En voor hem is het voordeel dat hij nu gedwongen is te schrijven, het proces van zijn onderzoek met zijn volgers te delen en zijn gedachten te structureren en te verwoorden."

2024

Interested in a challenging postdoc position in Amsterdam?

We are currently looking for a postdoc researcher that likes to work on the intersection of music cognition, biology, and the cognitive sciences. If you are excited about doing this kind of research in an interdisciplinary environment, with a team of smart and friendly colleagues, then you may want to join us.

More information, including details on how to apply, will be made available soon at our website.

Deadline for applications : 1 December 2024.

Interested in doing a PhD in Music Cognition?

Master students of the UvA (or excellent external candidates) are invited to submit a short proposal to be selected as a candidate for NWO's PhD in the Humanities programme.

Musical Animals: Are We? Can There Be?

Roughly ten years ago, I had the honor of being invited by the Barenboim-Said Akademie to deliver a public lecture in Berlin, Germany. The event, entitled Was Musik kann (What Music Can Do), celebrated the impact of music and musicianship on our lives. In my presentation I started with a listening experiment, in a playful attempt to challenge the audience.

I invited the attendees—many of whom were professional musicians and distinguished educators at the Barenboim-Said Academy—to envision themselves as expert judges on a conservatory selection committee. They were asked to assess the musicianship of an ensemble based solely on a brief excerpt of a live recording I played for them. Emulating the traditional audition process, where candidates perform behind a curtain to ensure impartiality, I asked the audience to make their judgments based solely on what they heard.

The audience's reaction was split; some were enthusiastic, while others were unimpressed. When asked for their thoughts, the positive responders praised the performance as experimental yet well-executed, whereas the negative ones criticized the timing as sloppy and the music as lacking melody. However, their opinions shifted dramatically after viewing a original video of the musicians: a group of Thai elephants, led by a human conductor, that were playing an array of percussion instruments and a mouth harmonica (see video registration).

This example is not just amusing; it also highlights some pitfalls in the study of the biology of music. Although I influenced the audience by framing the test as an audition, their varied reactions reveal more about human perception than about the elephants’ musical abilities. This raises a fundamental question: what must an organism—whether human, elephant, or bird—perceive to experience something as music? For instance, while the songs of an Amazonian songbird may sound musical to us, this perception reflects our own biases. To truly understand a bird's sense of musicality, we must ask whether the bird hears its own song as music. This inquiry shifts the attention from studying the structure of music to studying the structure of musicality.

Over the last two decades it has become evident that humans share a natural predisposition for music, akin to our inherent capacity for language (Hagoort, 2019). This predisposition, which I like to term musicality, encompasses a set of traits that develops spontaneously, is shaped by our cognitive abilities, as well being constrained by its underlying biology. Unlike music itself, which varies across cultures and societies, musicality refers to the cognitive and biological capacities that enable us to perceive and appreciate music, even among those who may not play an instrument or sing out of tune (Honing et al., 2015).

The shift in the study of the origins of music, from studying the structural aspects of music to trying to understand the structure of our capacity for music, marks an important change in perspective in music research, as reflected in the titles of two foundational meetings and their resulting publications: The Origins of Music (Wallin et al., 2000) and, consequently, The Origins of Musicality (Honing, 2018b). While the cross-cultural study of the structure of music (melodic patterns, scales, tonality, etc.) has offered exciting insights (Mehr et al., 2019; Savage et al., 2015), the approach used in these studies is indirect: the object of study here is music—the result of musicality—rather than musicality itself. Hence it is virtually impossible to distinguish between the individual contributions of culture and biology. For example, it is not clear whether the division of an octave into small and unequal intervals in a particular musical culture results from a widespread theoretical doctrine or from a music perception ability or a biological constrained predisposition.

All this is an important motivation to study the structure of musicality– i.e. the capacity for music–, its constituent components (see Table 1), and how these might be shared with other animals, aiming to disentangle the biological, cultural and environmental contributions to the human capacity for music. All these are topics that are elegantly addressed in the current volume.

[This text is a fragment of a preliminary version of an introductory chapter of The Biology of Music (Ravignani, in press)]

Ravignani, A. (ed.) (in press) The Biology of Music: Interdisciplinary Insights. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Do you know a parrot that talks or sings?

![Ben jij muzikaal? [Dutch]](/static/c182797325ca3ad26e476b9ec104d5a1/17e6c/thkids.png)

Ben jij muzikaal? [Dutch]

Why do humans sing? |ヒトはなぜ歌うのか

Below a trailer of a Japanese documentary on the origins of musicality, made by NHK, entitled Why do humans sing? (ヒトはなぜ歌うのか ).

The one hour documentary presents cross-species and cross-cultural research on musicality, realized and filmed in Amsterdam, Inuyama, Boston and the rainforest of Central Africa.

For more information see NHK | Frontiers.

A musical ape?

Music is universal in all human cultures, but why? What gives us the ability to hear sound as music? Are we the only musical species–or was Darwin right when he said every animal with a backbone should be able to perceive, if not enjoy music?

This episode was written and produced by Ray Pang and Meredith Johnson. Sound design, mixing, and scoring by Ray Pang. The editor is Audrey Quinn. Theme music by Henry Nagle, additional music by Blue Dot Sessions and Lee Roservere.

Listen to the podcast here.

Interested in the origins of musicality?

Next week prof. Aniruddh D. Patel will visit the Netherlands to discuss his work on the origins and evolution of musicality, with a public talk at the MPI Colloquium Series in Nijmegen on Tuesday 19 March 2024 and a scientific (invitation-only) workshop on Friday 22 March 2024 in Amsterdam.

N.B. The public talk can be viewed via MPI's live stream.

![Heb jij ritmegevoel? [Dutch]](/static/3aafcac7fe10e4e7bd2611cbb91e0e63/a45e6/uvn.jpg)

Heb jij ritmegevoel? [Dutch]

"Ritmegevoel, je denkt misschien dat je het niet hebt. Maar er is wereldwijd maar bij 6 mensen vastgesteld dat ze het verschil tussen ritmes écht niet kunnen horen. Je hebt dus wel degelijk ritmegevoel. Sterker nog... uit het onderzoek van Henkjan Honing (onderzoeker muziekcognitie aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam) blijkt dat dit niet alleen is aangeleerd, maar aangeboren. Zelfs baby's van een paar dagen oud hebben het door als je iets aan de regelmaat van muziek verandert. En ook sommige apen gaan spontaan bewegen op muziek. Hoe Henkjan hierachter kwam, en waarom we überhaupt ritmegevoel hebben, leer je in deze video."

Meer lezen? Hieronder enkele van de studies die genoemd worden in de video:

- Baby's : https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2023.105670

- Makaken : https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00475

- Chimpansees : https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1910318116

- Hersenen : https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00274

- Boek : Aap slaat maat: Op zoek naar de oorsprong van muzikaliteit bij mens en dier

- Wetenschappelijke video summary : ICMPC,Tokyo, J

2023

Feel like a musical memory challenge?

[Blog by Jiaxin Li on TeleTunes]

Think about your favorite TV show. Can you hear the theme music already starting to play in your mind? Maybe it’s the epic sounding strings from Game of Thrones or the punchy synthesizer from Seinfeld? You’ve probably heard the music from that show so many times it’s now encrypted in your memory. As music cognition researchers, we are eager to find out what makes some TV tunes more memorable than the others.

The TeleTunes game is designed for exactly this reason. It is a game that allows us to study the catchiness of TV themes. Unlike the Christmas or Eurovision versions of our Hooked-on Music game series, this game invites you to test your memory with clips from the most iconic TV themes, curated from IMDB’s 100 most watched shows and The Rolling Stone’s esteemed “Greatest” TV show lists spanning the past 40 years. Your challenge? If you recognise a tune, quickly click the button, sing along in your mind and judge whether after a few seconds it continues in the right spot.

Through engaging in this game, you are contributing to music science, enriching our understanding of musical memory. By investigating the familiarity of these TV tunes, we are building a corpus consisting of well-known music. In the near future, we will use the results for yet another game – TuneTwins – continuing our quest to investigate questions like “what makes music memorable” or even “how do we as human beings remember music”.

We hope you will enjoy this game. Each game takes only a few minutes, and you can play it as many times as you like. Listen carefully! The fewer mistake you make, the more points you’ll earn! Finally, feel free to share the link with your friends and family and see who can get the highest score. The more you play, the more you contribute to science!

TeleTunes can be found at: https://app.amsterdammusiclab.nl/teletunes.

Interested in a one-year postdoc position?

We are looking for a postdoc researcher that likes to work on the intersection of music cognition, psychometrics, and the cognitive sciences. If you are excited about doing this kind of research in an interdisciplinary environment, with a team of smart and friendly colleagues, then you may want to join us.

More information, including details on how to apply, can be found at the UvA website.

Deadline for applications : 15 January 2024.

Why did we decide to revisit and overhaul our earlier beat perception studies?

[Published in Scientific American and MIT Press Reader]

In 2009, we found that newborns possess the ability to discern a regular pulse – the beat – in music. It’s a skill that might seem trivial to most of us but that’s fundamental to the creation and appreciation of music. The discovery sparked a profound curiosity in me, leading to an exploration of the biological underpinnings of our innate capacity for music, commonly referred to as “musicality.”

In a nutshell, the experiment involved playing drum rhythms, occasionally omitting a beat, and observing the newborns’ responses. Astonishingly, these tiny participants displayed an anticipation of the missing beat, as their brains exhibited a distinct spike, signaling a violation of their expectations when a note was omitted. This discovery not only unveiled the musical prowess of newborns but also helped lay the foundation for a burgeoning field dedicated to studying the origins of musicality.

Yet, as with any discovery, skepticism emerged (as it should). Some colleagues challenged our interpretation of the results, suggesting alternate explanations rooted in the acoustic nature of the stimuli we employed. Others argued that the observed reactions were a result of statistical learning, questioning the validity of beat perception being a separate mechanism essential to our musical capacity. Infants actively engage in statistical learning as they acquire a new language, enabling them to grasp elements such as word order and common accent structures in their native language. Why would music perception be any different?

To address these challenges, in 2015, our group decided to revisit and overhaul our earlier beat perception study, expanding its scope, method and scale, and, once more, decided to include, next to newborns, adults (musicians and non-musicians) and macaque monkeys.

[...] Continue reading in The MIT Press Reader.

Do babies have a natural affinity for ‘the beat’ ?

‘There is still a lot we don't know about how newborn babies perceive, remember and process music,’ says author Henkjan Honing, professor of Music Cognition at the UvA. 'But, in 2009, we found clear indications that babies of just a few days old have the ability to hear a regular pulse in music – the beat – a characteristic that is considered essential for making and appreciating music.’

27 babies

Because the previous research from Honing and his colleagues had so far remained unreplicated and they still had many questions, the UvA and TTK joined forces once again – this time using a new paradigm. In an experiment with 27 newborn babies, researchers manipulated the timing of drum rhythms to see whether babies make a distinction between learning the order of sounds in a drum rhythm (statistical learning) and being able to recognize a beat (beat-induction).

Manipulated timing

The babies were presented with two versions of one drum rhythm through headphones. In the first version, the timing was isochronous: the distance between the sounds was always the same. This allows you to hear a pulse or beat in the rhythm. In the other version, the same drum pattern was presented, but with random timing (jittered). As a result, beat perception was not possible, but the sequence of sounds could be learned. This allowed the researchers to distinguish between beat perception and statistical learning.

Because behavioral responses in newborn babies cannot be observed, the research was done with brain wave measurements (EEG) while the babies were sleeping. This way, the researchers were able to view the brain responses of the babies. These responses showed that the babies heard the beat when the time interval between the beats was always the same. But when the researchers played the same pattern at irregular time intervals, the babies didn't hear a beat.

Not a trivial skill

‘This crucial difference confirms that being able to hear the beat is innate and not simply the result of learned sound sequences,’ said co-author István Winkler, professor at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience and Psychology at TTK. 'Our findings suggest that it is a specific skill of newborns and make clear how important baby and nursery rhymes are for the auditory development of young children. More insight into early perception is of great importance for learning more about infant cognition and the role that musical skills may play in early development.'

Honing adds: 'Most people can easily pick up the beat in music and judge whether the music is getting faster or slower – it seems like an inconsequential skill. However, since perceiving regularity in music is what allows us to dance and make music together, it is not a trivial phenomenon. In fact, beat perception can be considered a fundamental human trait that must have played a crucial role in the evolution of our capacity for music.’

Publication details

Gábor P. Háden, Fleur L. Bouwer, Henkjan Honing and István Winkler. Beat processing in newborn infants cannot be explained by statistical learning based on transition probabilities, Cognition, DOI 10.1016/j.cognition.2023.105670.

[Source UvA Press Office: English version; Dutch version.]

Interested in doing a PhD in Music Cognition?

Master students of the UvA (or excellent external candidates) are invited to submit a short proposal to be seleted as candidate for NWO's PhD in the Humanities programme.

How to keep a forest happy?

A new study on the possible evolutionary origins of music [Press Release]

[Newspaper article in Dutch]

Why is music so prevalent and universal in human societies? Does music serve an adaptive function, or it is just “auditory cheesecake”, as cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker infamously claimed: a delightful dessert but, from an evolutionary perspective, no more than a by-product of language?

The debate on the origins of music has intrigued scientists for centuries. The hypotheses range from music being a mating display in order to woo females, to a means to increase social bonding in group contexts. For the first time, a group of international and interdisciplinary researchers led by Karline Janmaat and her former MSc Student Chirag Chittar, have tested several hypotheses on music simultaneously in a modern foraging society during their daily search for food. They found that women during tuber finding events were more likely to sing in large groups of strangers and less likely to sing in large groups of individuals they knew. The study was part of an elaborate longitudinal study spanning 2 years and has now been published in Frontiers in Psychology.

Music makes the forest happy

“We know from their communication about music that the BaYaka sing to “please the forest” so that it provides them with more food. What they dislike most is conflict, as they believe it would make the forest spirits angry. What intrigues me the most is that our behavioral observations nicely complement their verbal communication about music. The women sing more frequently when they search for food in groups that are large and contain fewer “friends”, in which conflicts about food are more likely to arise. To me, our study reveals that these foragers appear to use music as a tool to avoid potential future conflict. How amazing is that?!”, Janmaat says.

“This study gives important empirical insights in the possible origins of music, a topic that for long had to be mere speculation”, says coauthor Henkjan Honing, professor of Music Cognition at UvA. “It made us decide to intensify our interdisciplinary collaboration and to further study the role of music with the BaYaka in a project aiming to unravel the human capacity for music. We are excited to announce our plans to return to this captivating society next year, where music appears to occupy a central role that transcends language.”

Chittar, C., Jang, H., Samuni, L, Lewis, J, Honing, H., Van Loon, E.E., Janmaat, K.R.L. (2023). Music and its role in signaling coalition during foraging contexts in a hunter-gatherer society. Frontiers in Psychology. doi 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1218394.

Interested in contributing to our web-based music science platform?

More information on how to apply can be found here.

Deadline for applications is 31 October 2023.

Did you enjoy playing the game Memory?

Did you enjoy playing the game Memory as a child? You can now play the game with music instead of pictures! Say hello to the TuneTwins!

Researchers from the Music Cognition Group at the University of Amsterdam developed this game to answer important scientific questions about our perception and memory of music.

In TuneTwins, you are challenged to match identical or similar tune pairs. These are taken from the 100 most popular TV themes according to IMDB and The Rolling Stone!

Each game would only take a few minutes and you are welcome to play it as many times as you want. The more you play, the more you contribute to science!

You can find a tutorial and a link to the game here.

What is your position on the possible origins of music/ality?

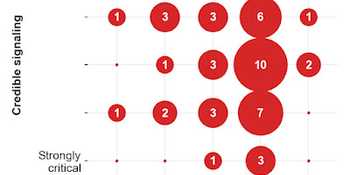

This blog-entry adds several new analyses and visualizations related to the topic of the origins of music/ality, as discussed in a recent issue of Behavioral and Brain Sciences (BBS; cf. Mehr et al., 2021; Savage et al., 2021).

N.B. An interactive app, linking to the two target articles, the 60 commentaries, as well as the commentaries' position in this debate, can be found on GitHub.

The analyses presented below are based on a questionnaire that was send to the 60 commentary writers in 2021.

Fig. 1 shows the outcome of that questionnaire asking to rate one's own position w.r.t. the two target articles on a five point scale from Strongly Critical to Strongly Supportive (N.B. We received 49 responses):

Fig. 2 below shows the rating provided by Savage et al. (2021), where two raters judged the positions of all commentaries on the same two dimensions (but on a continuous scale):

Furthermore, we also did some simple numerical comparisons between the data presented in Fig. 1 and 2. The main observations are:

-

For the Social Bonding hypothesis there is an agreement* between ratings shown in Fig. 1 and those of Fig.2 of <b>.62</b> (Rater 1/Authors) and <b>.69</b> (Rater 2/Authors). As such, the raters did a relatively good job in estimating the authors positions. </li><li>For the Credible Signalling hypothesis the agreement* was <b>.51</b> (Rater 1/Authors) and <b>.56</b> (Rater 2/Authors), suggesting the raters did less well in estimating the authors positions.<br></li></ol><p>*Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). Note that resolution of both ratings (Fig. 1 and 2) differ, which could affect the results.

Fig 3. shows the results on the question whether this two-dimensional representation was considered adequate by the commentary authors:

[Credits: Visualizations by Bas Cornelissen; Stats by Atser Damsma]

Mehr, S., Krasnow, M., Bryant, G., & Hagen, E. (2021). Origins of music in credible signaling. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 44, E60. doi:10.1017/S0140525X20000345

Savage, P., Loui, P., Tarr, B., Schachner, A., Glowacki, L., Mithen, S., & Fitch, W. (2021). Music as a coevolved system for social bonding. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 44, E59. doi:10.1017/S0140525X20000333

Honing, H. (2021). Unravelling the origins of musicality: Beyond music as an epiphenomenon of language. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 44, E78. doi:10.1017/S0140525X20001211

2022

Interested in becoming Assistant Professor in Generative AI in Amsterdam?

Generative AI in the past decade has changed the field of artistic creativity, making us ask new questions that are relevant not only for scientific research but also for musicians and artists of all kinds. With this position, we are seeking to broaden our profile with respect to AI-assisted music generation and how AI-generated art can be positioned within the humanities and cognitive science more generally. The explosive growth of creative AI has also brought new ethical and epistemological dimensions to reflect upon, and we are looking for a colleague who can translate this reflection into both teaching and research. The ideal candidate will be somebody comfortable engaging in the ethics and implications of using AI in artistic processes regardless of medium, with more specific expertise in how AI is (and can be) used to make music.

See here for all information on how to apply.

Deadline for applications: 12 January 2023.

Wat is een absoluut gehoor en is het erfelijk? [Dutch]

Niet zo lang geleden verscheen op het internet een video [zie hieronder een nwe versie] met de tekst: ‘Kijk eens wat deze hond kan. Hij is muzikaler dan ik!’

De video laat een golden retriever zien die geconcentreerd naar zijn baas kijkt die tegenover hem zit. Als zij een toon laat horen reageert de hond door met zijn poot een toets in te drukken op een fors pianotoetsenbord dat voor hem op de grond ligt. Welke toon het baasje ook speelt, de hond herhaalt zonder aarzeling precies dezelfde toon op de piano. ‘Hij heeft absoluut gehoor!’ voegt een lezer al snel als commentaar aan de video toe. En dat klopt. De meeste dieren hebben absoluut gehoor, in de zin dat zij klanken onthouden en herkennen aan de absolute frequentie (het trillingsgetal) van het geluid, en niet zozeer aan het melodische verloop of de intervalstructuur, zoals wij mensen dat doen. Wij vinden absoluut gehoor daarom bijzonder. Als je aan musici vraagt een voorbeeld te noemen van een bijzondere muzikale vaardigheid dan noemen velen als eerste ‘absoluut gehoor’. Iemand met een absoluut gehoor kan een willekeurig aangeslagen pianotoon benoemen zonder gezien te hebben welke toets er werd ingedrukt. Vooral voor conservatoriumstudenten is dat handig, omdat zij dan minder moeite hebben met de muzikale dictees die ze regelmatig krijgen: het in notenschrift opschrijven van wat de docent voorspeelt of zingt.

Maar terug naar de golden retriever. Ik denk dat hij inderdaad de pianotonen aan hun frequentie kan herkennen. Maar ik vermoed ook dat als er een gordijn tussen hem en zijn baasje gehangen wordt, hij deze ingewikkelde taak niet meer vlekkeloos uitvoert. Deze hond doet immers meer dan alleen een toon herkennen aan zijn trillingsgetal. De term absoluut gehoor is wat dat betreft te beperkt. De hond moet namelijk behalve een toon horen, herkennen en herinneren, deze ook classificeren (is het een c of een cis?), bepalen welke toets daarbij hoort en deze vervolgens aanslaan op het grote toetsenbord dat voor hem ligt. Op de video zijn de ogen van de golden retriever en die van zijn eigenaar niet te zien, maar het zou me niet verbazen als de hond vooral haar blik volgt om te weten welke toets hij verwacht wordt aan te slaan, in plaats van zijn absolute gehoor. Het zou heel goed kunnen dat het klassieke Pavlov-effect – als ik doe wat baasje van mij verlangt, krijg ik een beloning – hier sterker is. (Dit is eenvoudig te testen door een gordijn tussen hond en baas te hangen. Voorspelling: de hond kan de taak niet meer vlekkeloos uitvoeren.)

Absoluut gehoor is dus niet zo zeer een gehoorvaardigheid, zoals de term suggereert, als wel een cognitieve vaardigheid. Het bestaat uit zeker twee aspecten: je moet je een toon kunnen herinneren en vervolgens een naam geven. Daarnaast moet je voor dat laatste een toon – of hij nou door een piano, viool, stem of fluit wordt voortgebracht – kunnen classificeren als behorende tot eenzelfde categorie en hem vervolgens benoemen.

Het eerste is een wijdverspreide vaardigheid die je eenvoudig kan testen. Stel je een bekend liedje voor, bijvoorbeeld Stayin’ alive van de Beegees, en zing het vervolgens. Grote kans dat de toonhoogte precies overeenkomt met het origineel. Wij mensen kunnen (net als veel andere dieren) heel goed de toonhoogte onthouden van bijvoorbeeld popliedjes of tv-tunes die we goed kennen. Maar een enkele toon horen en vervolgens weten of het een c is of een cis is een bijzondere vaardigheid die bij minder dan 1 op de 10.000 mensen voorkomt.

Er zijn goede reden om absoluut gehoor te zien als het resultaat van een genetisch bepaalde aanleg. Diverse studies laten zien dat bepaalde chromosomen betrokken zijn bij het wel of niet hebben van de vaardigheid (zoals chromosoom 8q24.21). Daarnaast zijn er neurowetenschappelijke studies die anatomische verschillen tussen mensen met en zonder absoluut gehoor laten zien, met name in de temporaalkwab en diverse corticale gebieden.

Niet alleen lijkt absoluut gehoor een genetische component te hebben en dus erfelijk te zijn, het ontwikkelen ervan is hoogstwaarschijnlijk het resultaat van blootstelling aan muziek op jonge leeftijd en intensieve muzikale training. In een land als Japan komt absoluut gehoor veel vaker voor dan elders. Bij Japanse conservatoriumstudenten loopt het percentage soms op tot wel 70 procent. Dat zou verklaard kunnen worden door het feit dat het een land is waar muziek een belangrijke plaats heeft in het onderwijs aan jonge kinderen.

Maar voor zover we weten heeft absoluut gehoor niet zo veel met muzikaliteit te maken heeft. Mensen met absoluut gehoor zijn over het algemeen niet muzikaler dan andere mensen. Sterker nog: de overgrote meerderheid van de westerse professionele musici heeft helemaal geen absoluut gehoor.

Ivan Pavlov ontdekte al in het begin van de vorige eeuw dat honden een enkele toon konden onthouden en associëren met bijvoorbeeld eten. Ook van wolven, en ratten, is bekend dat zij soortgenoten herkennen aan de absolute toonhoogte van hun roep, en dus onderscheid kunnen maken tussen de ene en de andere toon. En voor spreeuwen en resusapen, is dat niet anders, zo suggereren verschillende studies.

Een veel muzikaler vaardigheid is ‘relatief gehoor’ – het herkennen van een melodie, los van de precieze toonhoogte waarop die klinkt of gezongen wordt. De meeste mensen luisteren niet naar de afzonderlijke tonen en hun trillingsgetal, maar naar de melodie als geheel. Of we Altijd is Kortjakje ziek nou lager of hoger gezongen horen worden, we herkennen het liedje toch wel.

Het horen van verbanden en relaties tussen de tonen, in zowel melodische als harmonische zin, is deel van het plezier van het luisteren naar muziek. Het maakt de vraag of we relatief gehoor met andere diersoorten delen, inclusief honden, een van de centrale vragen in het onderzoek naar de biologische basis van de menselijke muzikaliteit.

Uit: Honing, H. (2017). Wat is een absoluut gehoor en is het erfelijk? In Rinnooy Kan & de Graaf (eds.), Hoe zwaar is licht? (pp. 74-76). Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Balans.

![Wil je ontdekken hoe het zit met je absoluut en relatief gehoor? [Dutch]](/static/bf353ff6d9cedf93a71dc8b0efd37ff0/e21b2/atlas.jpg)

Wil je ontdekken hoe het zit met je absoluut en relatief gehoor? [Dutch]

Kun jij horen welke versie van de intro van Wie de mol? of The Walking Dead de juiste toonhoogte heeft? En lukt het je om van een superkort fragment de titel en artiest van een nummer herkennen? Ontdek hoe het zit met je absoluut en relatief gehoor, je gevoel voor ritme en timing, en je geheugen voor muziek. Je bent waarschijnlijk muzikaler dan je denkt. Speel de mini-games op ToontjeHoger en leer tegelijkertijd meer over muzikaliteit.

ToontjeHoger is ontwikkeld door de muziekcognitiegroep van de Universiteit van Amsterdam. Speel de minigames hier.

Can you do better than a songbird?

Note that –like the zebra finches– you will get no explicit instruction, just some simple feedback on whether your answer is correct (smiley), incorrect (sad face), or not in time (question mark).

After this you will enter the main phase of the experiment in which you

are asked to simply continue responding to the sound sequences as you

did before. Note that, in this final phase, you will only occasionally

receive feedback.

Can you do as well, or even better than a songbird?

The online experiment can be found here.

Interested in doing a PhD in music cognition?

Are we born to be musical?

This is the first episode of The Rhythm of Life, a series from BBC Reel exploring the power of music.

![Waarom kunnen sommige mensen niet dansen? [Dutch]](/static/a3392b815e2c11d8cd3ffda1cb15c5e5/d5c9f/FB.jpg)

Waarom kunnen sommige mensen niet dansen? [Dutch]

Het Amsterdam Dance Event is begonnen. Waarom kunnen sommige mensen niet dansen?

Een gesprek met neurowetenschapper Fleur Bouwer van de Universiteit van Amsterdam. De aflevering is hier te vinden.

![Wanneer is muziek raar? [Dutch]](/static/e3a17d6a2b641343730b86a89ee23a26/d5c9f/3kih8pvmkoak-kn-de-nacht-livetegel-def.jpg)

Wanneer is muziek raar? [Dutch]

Voor wie graag naar unieke klanken luistert is 24 augusutus de ideale dag. Deze dag staat namelijk in het teken van 'Strange Music'. Het idee hierachter? Mensen kennis laten maken met klanken en melodieën die net buiten de gebaande paden treden.

Maar wat is nu eigenlijk strange music? Kunnen we bepaalde muziek wel globaal bestempelen als raar? Of schuilt hier toch meer achter?

Presentator Benji Heerschop spreekt hierover met hoogleraar muziekcognitie Henkjan Honing.

![Is muziek niet grotendeels cultureel bepaald? [Dutch]](/static/a7634ee98e45eebb13a6013b2f01de77/a45e6/D5CAE501-FBB2-4E46-A255-1B143F265B6C_1_102_o.jpg)

Is muziek niet grotendeels cultureel bepaald? [Dutch]

Interview met Henkjan Honing in de Volkskrant door Cécile Koekkoek:

"Voor de onregelmatige reeks over intuïtie, waarvoor V spreekt met deskundigen uit verschillende vakgebieden, schakelt hoogleraar muziekwetenschap Henkjan Honing (63) in via zoom vanuit zijn vakantieadres in Frankrijk. ‘Ik heb niks voorbereid, dus ik antwoord op intuïtie’, zegt hij lachend. Hij komt meteen to the point. ‘Er zijn twee vormen van weten. Het ene weten gaat uit van ervaring en het andere weten van rationele kennis. Oftewel: van impliciete en expliciete kennis. Als wetenschapper laveer je voortdurend tussen die twee."

Interested in doing a PhD in Amsterdam?

All information on how to apply can be found here.

Deadline for applications is 21 July 2022.

Was Darwin right? (New book, translated in German and Italian)

Appraisal of The Evolving Animal Orchestra (MIT Press):

"In 1871 Charles Darwin argued :

The perception, if not the enjoyment, of musical cadences and of rhythm is probably common to all animals.

Henkjan Honing has tested this eminent reasonable idea, and in his bookhe reports back. He details his disappointment, frustration and downright failure with such wit, humility and a love of the chase that any young person reading it will surely want to run away to become a cognitive scientist."

–– Simon Ings in NewScientist.

"Honing’s new

book provides a succinct, informal though rigorous overview of what we know of cross-species musicality. [..] Most science happens as a tiresome journey, and what the public sees is only the splendidness of arrival – that's not the case of this book. This is a popular science book, intriguing and entertaining."

–– Andrea Ravignani in Current Biology.

"Originally published in 2018 in the Netherlands, the new English translation by Sherry MacDonald has been eagerly awaited by students and scholars who are curious about music’s place beyond the strictly human. I believe they will not be disappointed, for Honing’s book offers a number of insights for both the amateur and the scientist in a readable prose style."

–– Rachel Mundy in Psychology of Music.

For more endorsements, see here.

For related podcasts, see HedgehogandtheFox and BigBiology.

For related documentaries, see CBC, Sky Tv and here.

For links to all the books, see here.

Do language and music share one precursor?

One way of categorizing the sensitivities of animals to the building blocks of language and music is to group these sensitivities along the frequency/spectral and temporal dimensions of sound. Although speech and music share many acoustic features, music appears to take advantage of a different set of acoustic features than speech. In humans the frequency dimension is central to music/melody perception, while for understanding speech the temporal dimension appears to be most fundamental (Albouy et al., 2020; Shannon et al., 1995). With respect to the frequency dimension of speech, humans attend primarily to the spectral structure (which enables the distinction between

the different vowels and consonants), while for music the attention appears to be less on a spectral quality (e.g., the sound of a guitar versus that of a flute), but instead on the melodic and rhythmic patterns. As such, it might well be that humans are an exception in that they can interpret the same sound signal in (at least) two distinct ways: as speech or as music (cf. speech-to-song illusion). In other animals such distinction is not observed (as yet). In humans, melody and speech are processed along specific and distinct neural pathways (Albouy et al., 2020; Norman-Haignere et al., 2022) and it could be that brain networks that support musicality are partly recycled for language (Peretz et al., 2018). This could imply that both language and music share one precursor. In fact, it is one possible route to test the Darwin-inspired conjecture that musicality precedes music and language (Honing, 2021). In a recent preprint (ten Cate & Honing, 2022) we discuss the potential components of such a precursor.

Albouy, P., Benjamin1, L., Morillon, B., & Zatorre, R. J. (2020). Distinct sensitivity to spectrotemporal modulation supports brain asymmetry for speech and melody. Science, 367(6481), 1043–1047. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaz3468.

Honing, H. (2021). Unravelling the origins of musicality: Beyond music as an epiphenomenon of language. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 44(E78), 66–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X20001211.

Norman-Haignere, S. V., Feather, J., Boebinger, D., Brunner, P., Ritaccio, A., McDermott, J. H., … Kanwisher, N. (2022). A neural population selective for song in human auditory cortex. Current Biology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.01.069.

Peretz, I., Vuvan, D. T., Armony, J. L., Lagrois, M.-É., & Armony, J. L. (2018). Neural overlap in processing music and speech. In H. Honing (Ed.), The Origins of Musicality (Vol. 370, pp. 205–220). Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0090.